RIDGE and American Oak

Blog Post

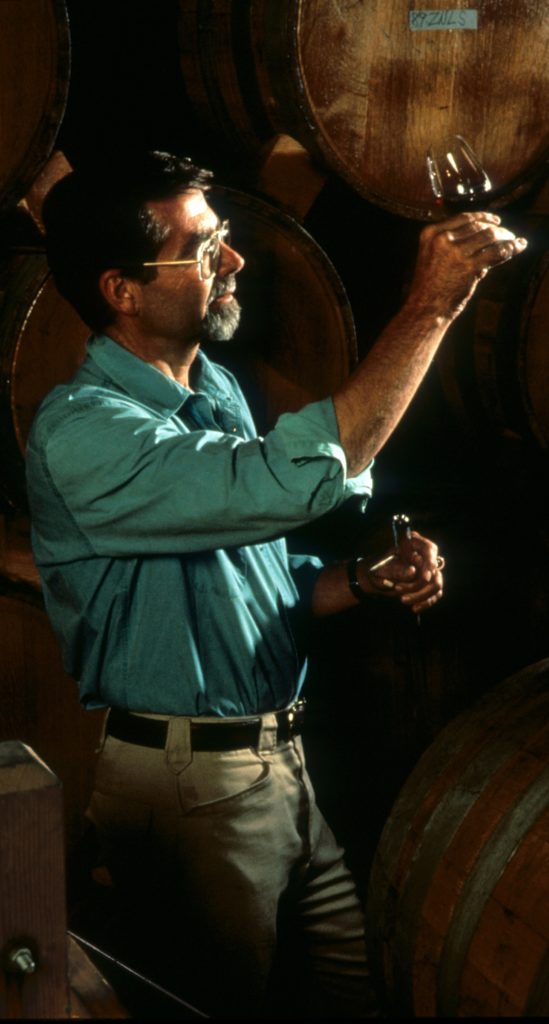

Longtime Winemaker and Ridge Chairman, Paul Draper, thinks back on his time as a winemaker in Chile and discusses his decision to use American oak at Ridge:

Paul Draper: “In the U.S. sourcing barrels is fairly straight forward. However, as I learned sourcing oak barrels in Chile is difficult. We had to source indigenous oak and collaborate with local barrel makers to obtain the wine barrels we needed. It did give us a greater understanding of each part of the process. For example, it forced me to think about oak sources and the handling of oak very early on. Someone who helped educate me was a young Frenchman, Phillippe Dourthe. He had his degree in enology from the University of Bordeaux and his family was in the wine business there. At that time the French government offered students an alternative to military service. Instead of going into the army, they were allowed to work as technicians in developing countries. Phillippe and another friend had been assigned to teach enology at the University of Chile and to work in the extension service with Chilean growers and wineries.

“I saw him quite often and we became good friends. We would discuss anything and everything related to wine. I was very interested in the idea of using American oak rather than French oak, and in Chile I was using Chilean oak – that is, trees grown and cut in Chile. He knew that by this time I was looking toward the future and that, at some point, I would be moving back to California to work in winemaking there. He mentioned that he had written his enology thesis at the University of Bordeaux on the oak-aging of wines. The most important research he used in the thesis had been a study done in Bordeaux with the vintage of 1900 (in fact a very, very good vintage), because back in the nineteenth century the French had been more interested in oak. The University of Bordeaux enological station had placed two barrels each of six different oaks – that is oaks from six different regions – and into these went a series of the first growths of that day: Latour, Lafite, Margaux, Haut-Brion, and two other chateaux. They then aged out the 1900 vintage wines in those barrels for the then-typical two-and-a-half to three years.

“During those years in barrel and for seven more years in bottle, they analyzed and tasted the wine. The researchers had thought there might be an ideal oak for each of the regions- -for Graves, Margaux, and Pauillac, and maybe even for each of the terroirs of the individual sites, that they would prefer one oak with one chateau and another with another.

“In fact, as it turned out, that statistically they found they agreed on the finest oak, and that it was the best for all the chateaux. There was very minor deviation, where it moved into second place in one chateau and then moved back into first. But effectively the result was that the European oak, cut from the area of Riga, in Latvia, on the Baltic, was their favorite.

“Their second favorite I believe was Lubeck, also on the Baltic, in the area near the Polish German border. The third area, also on the Baltic, was Stettin in Germany. Their fourth favorite was American white oak. Fifth was Bosnian, Yugoslav oak. Their last was “Center of France,” and that is the source of the majority of the French cooperage used in California, let alone, of course, in France. It is referred to as the “Center of France” and includes the areas of Nevers, Tronce, Alliers, and neighboring regions.

“Phillippe’s encouragement and that study convinced me to experiment with American oak and to use it if it proved its quality.”

We continue the discussion on American oak and its use at Ridge below.

The First RIDGE Cooperage Trials

Ridge purchased new American and French oak barrels in 1974 to conduct trials. The American barrels came from the Ozarks from a cooperage that had an oversupply of staves that air-dried seven years. Those staves were selected by Paul Draper to be used to make the barrels in a bourbon size and with careful toasting. The Demptos French barrels were roughly $50 duties paid, the American were $35. Price between the two were not as radical as today’s prices. Back then Paul could have selected French oak if he felt it was the better choice of oak to use for Ridge wines. The cost between the two oak types was never a factor in making the decision to go with American oak. Also, Monte Bello vineyard’s tannic grapes, making a wine that tastes similar to Bordeaux, were better suited to American oak to taste unique and different. Paul and the Ridge founders did not want to make imitation Bordeaux. American oak is twice as dense as French, carrying greater spice and wood sugar compounds that slowly extract and fill out a wine’s body. In the case of Monte Bello, with high tannin content, the American oak sweetness coats the tannins and helps make the wine more sensuous and exotic. In fact, the beautiful toasted oak notes of American oak can help cover some of the herbaceousness of cabernet sauvignon. Monte Bello is in a cool location, the Bordeaux grapes grown there can often have an element of herbaceousness. The American oak has been key to helping the wine settle down and integrate the tobacco and olive notes within the toasted oak flavors and aromas.

American Oak vs French Oak

Production Methods

High quality American oak wine barrels are typically air-dried 24-36 months. The wood is seasoned in the forest environment where there is four seasons, summer rains and humidity. To even out the seasoning, the wood has to be carefully stacked with air gaps to allow air movement. The ricks of wood have to be torn down and restacked bottom to top/top to bottom so that it is uniformly seasoned. During this time, mycelia growth breaks down compounds in American oak to liberate wood sugars. After enough time the wood can be taken into the stave mills for barrel production. To soften the wood to make it flexible, the wood must be steamed or put over a fire pot and wetted down to allow it to become soft enough to flex as the body of the barrel is shaped and hoops installed. Steam has always been our favorite method of barrel bending. It opens up the pours and prepares the wood for toasting. Once the barrel is put on the fire pot for toasting, any tannins that are present in American oak will be burnt off and oak sugars caramelized. The aroma coming from a freshly made barrel is much like a cinnamon and sugar dusted graham cracker. It’s extremely sweet and exotic smelling.

With air-dried French oak, barrel bending is done through fire and wetting down barrel as its bent. Depending on the toasting, tannins can be reduced through time and temperature of being on a fire pot. An elegant toast will retain a lot of wood tannin, a heavier toast will reduce it. Nevertheless, it contains so much tannin that even a heavy toast will still produce a tannic finish in a wine. French oak does not contain as much sweetness in the wood to produce any caramelized sugar notes. It’s mostly just vanilla on the nose of a new French oak barrel.

Tannin

In grapes, tannins are in the skins (10%) and seed (90%), not just the skins. Seed and skin tannins combine during fermentation. Those compounds are the textural element of wine. Unbound “free” tannins are the ones responsible for astringency and dryness. French oak elagotannins (wood tannins) extract after fermentation and therefore don’t have the chance to integrate. They will increase the astringency, making a wine more grainy and dry in the finish.

The tannin content of French oak is significantly greater than American oak. American oak contains mostly spice and complex five-carbon wood sugars, which caramelize during barrel toasting, with virtually no tannins (if seasoned correctly.) Those complex sugars extract into the wine, providing a sweetness to masque the grape derived tannins of the wine. The finish of a tannic cabernet aged in American oak will be rounder, softer, and showing sweeter fruit.

For cabernet vineyards that have high yields, are irrigated, that have juicy grapes of low tannin content, French oak is necessary to provide the wine some texture and tannin structure. Additionally, as a way to augment the wine’s tannins structure, many winemakers make use of powdered French oak by adding it to the crushed grapes during fermentation.

Aromatics

French oak contains mostly the aromatic compound vanillin, which gives wines a vanilla flavor. Due to the greater porosity of French oak, vanillin is intensely extracted into wine to a high degree. Its potency will make a wine taste monolithic and heavy. It will create a vail over a wine’s vineyard character or varietal notes. It’s akin to heavy use of cosmetics. American oak, if air-dried appropriately, will not show strong notes of dill or coconut. Due to American oak’s density, being less porous, that leads to a gentle extraction of clove, nutmeg, brown sugar aroma and flavors. It does not overpower and mask cabernet’s aromas. If anything, those cabernet fruit aromas and flavors are elevated and enhanced by American oak.

Stay up-to-date with the latest RIDGE news, wine releases, and special offers – join our mailing list.

Wait!

In order to qualify for user related discounts, you must log in before proceeding with checkout. Click the button below to log in and receive these benefits, or close the window to continue.

Log In